Nucleon

- For the Ford concept car, see Ford Nucleon. For the fictional power source in the Transformers universe, see Nucleon (Transformers).

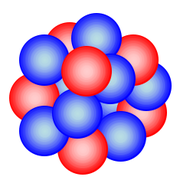

In physics, a nucleon is a collective name for two particles: the neutron and the proton. These are the two constituents of the atomic nucleus. Until the 1960s, the nucleons were thought to be elementary particles. Now they are known to be composite particles, each made of three quarks bound together by the so-called strong interaction.

The interaction between two or more nucleons is called internucleon interactions or nuclear force, which is also ultimately caused by the strong interaction. (Before the discovery of quarks, the term "strong interaction" referred to just internucleon interactions.)

Nucleons sit at the boundary where particle physics and nuclear physics overlap. Particle physics, particularly quantum chromodynamics, provides the fundamental equations that explain the properties of quarks and of the strong interaction. These equations explain quantitatively how quarks can bind together into protons and neutrons (and all the other hadrons). However, when multiple nucleons are assembled into an atomic nucleus (nuclide), these fundamental equations become too difficult to solve directly (see lattice QCD). Instead, nuclides are studied within nuclear physics, which studies nucleons and their interactions by approximations and models, such as the nuclear shell model. These models can successfully explain nuclide properties, for example, whether or not a certain nuclide undergoes radioactive decay.

The proton and neutron are both baryons and both fermions. In the terminology of particle physics, these two particles make up an isospin doublet (I = 1⁄2). This explains why their masses are so similar, with the neutron just 0.1% heavier than the proton.

Contents |

Nucleon properties

Protons and neutrons are most important and best known for constituting atomic nuclei, but they can also be found on their own, not part of a larger nucleus. A proton on its own is the nucleus of the hydrogen-1 atom (1H). A neutron on its own is unstable (see below), but they can be found in nuclear reactions (see neutron radiation) and are used in scientific analysis (see neutron scattering).

Both the proton and neutron are made of three quarks. The proton is made of two up quarks and one down quark, while the neutron is one up quark and two down quarks. The quarks are held together by the strong force. It is also said that the quarks are held together by gluons, but this is just a different way to say the same thing (gluons mediate the strong force).

An up quark has electric charge +2⁄3 e, and a down quark has charge −1⁄3 e, so the total electric charge of the proton and neutron are +e and 0, respectively. The word "neutron" comes from the fact that it is electrically "neutral".

The mass of the proton and neutron is quite similar: The proton is 1.6726×10−27 kg or 938.27 MeV/c2, while the neutron is 1.6749×10−27 kg or 939.57 MeV/c2. The neutron is roughly 0.1% heavier. The similarity in mass is explained by the isospin approximate-symmetry in particle physics (also see below).

The spin of both protons and neutrons is 1⁄2. This means they are fermions not bosons, and therefore, like electrons, they are subject to the Pauli exclusion principle. This is a very important fact in nuclear physics: Protons and neutrons in an atomic nucleus cannot all be in the same quantum state, but instead they spread out into nuclear shells analogous to electron shells in chemistry. Another reason that the spin of the proton and neutron is important is because it is the source of nuclear spin in larger nuclei. Nuclear spin is best known for its crucial role in the NMR/MRI technique for chemistry and biochemistry analysis.

The magnetic moment of a proton, denoted μp, is 2.79 nuclear magnetons (μN), while the magnetic moment of a neutron is μn = −1.91 μN. These parameters are also important in NMR/MRI.

Stability of nucleons

A neutron by itself is an unstable particle: It undergoes β− decay (a type of radioactive decay) by turning into a proton, electron, and electron antineutrino, with a half-life around ten minutes. (See the Neutron article for further discussion of neutron decay.) A proton by itself is thought to be stable, or at least its lifetime is too long to measure. (This is an important issue in particle physics, see Proton decay.)

Inside a nucleus, on the other hand, both protons and neutrons can be stable or unstable, depending on the nuclide. Inside some nuclides, a neutron can turn into a proton (plus other particles) as described above; inside other nuclides the reverse can happen, where a proton turns into a neutron (plus other particles) through β+ decay or electron capture; and inside still other nuclides, both protons and neutrons are stable and do not change form.

Antinucleons

Both of the nucleons have corresponding antiparticles: The antiproton and the antineutron. These antimatter particles have the same mass and opposite charge as the proton and neutron respectively, and they interact in the same way. (This is generally believed to be exactly true, due to CPT symmetry. If there is a difference, it is too small to measure in all experiments to date.) In particular, antinucleons can bind into an "antinucleus". So far, scientists have created antideuterium[1][2] and antihelium-3[3] nuclei.

Quark model classification

In the quark model with SU(2) flavour, the two nucleons are part of the ground state doublet. The proton has quark content of uud, and the neutron, udd. In SU(3) flavour, they are part of the ground state octet (8) of spin 1⁄2 baryons, known as the Eightfold way. The other members of this octet are the hyperons strange isotriplet Σ+, Σ0, Σ−, the Λ and the strange isodoublet Ξ0, Ξ−. One can extend this multiplet in SU(4) flavour (with the inclusion of the charm quark) to the ground state 20-plet, or to SU(6) flavour (with the inclusion of the top and bottom quarks) to the ground state 56-plet.

The article on isospin provides an explicit expression for the nucleon wave functions in terms of the quark flavour eigenstates.

Models

Although it is known that the nucleon is made from three quarks, as of 2006[update], it is not known how to solve the equations of motion for quantum chromodynamics. Thus, the study of the low-energy properties of the nucleon are performed by means of models. The only first-principles approach available is to attempt to solve the equations of QCD numerically, using lattice QCD. This requires complicated algorithms and very powerful supercomputers. However, several analytic models also exist:

The Skyrmion models the nucleon as a topological soliton in a non-linear SU(2) pion field. The topological stability of the Skyrmion is interpreted as the conservation of baryon number, that is, the non-decay of the nucleon. The local topological winding number density is identified with the local baryon number density of the nucleon. With the pion isospin vector field oriented in the shape of a hedgehog, the model is readily solvable, and is thus sometimes called the hedgehog model. The hedgehog model is able to predict low-energy parameters, such as the nucleon mass, radius and axial coupling constant, to approximately 30% of experimental values.

The MIT bag model confines three non-interacting quarks to a spherical cavity, with the boundary condition that the quark vector current vanish on the boundary. The non-interacting treatment of the quarks is justified by appealing to the idea of asymptotic freedom, whereas the hard boundary condition is justified by quark confinement. Mathematically, the model vaguely resembles that of a radar cavity, with solutions to the Dirac equation standing in for solutions to the Maxwell equations and the vanishing vector current boundary condition standing for the conducting metal walls of the radar cavity. If the radius of the bag is set to the radius of the nucleon, the bag model predicts a nucleon mass that is within 30% of the actual mass. An important failure of the basic bag model is its failure to provide a pion-mediated interaction.

The chiral bag model merges the MIT bag model and the Skyrmion model. In this model, a hole is punched out of the middle of the Skyrmion, and replaced with a bag model. The boundary condition is provided by the requirement of continuity of the axial vector current across the bag boundary. Very curiously, the missing part of the topological winding number (the baryon number) of the hole punched into the Skyrmion is exactly made up by the non-zero vacuum expectation value (or spectral asymmetry) of the quark fields inside the bag. As of 2006[update], this remarkable trade-off between topology and the spectrum of an operator does not have any grounding or explanation in the mathematical theory of Hilbert spaces and their relationship to geometry. Several other properties of the chiral bag are notable: it provides a better fit to the low energy nucleon properties, to within 5–10%, and these are almost completely independent of the chiral bag radius (as long as the radius is less than the nucleon radius). This independence of radius is referred to as the Cheshire Cat principle, after the fading to a smile of Lewis Carroll's Cheshire Cat. It is expected that a first-principles solution of the equations of QCD will demonstrate a similar duality of quark-pion descriptions.

See also

References

- Gerald Edward Brown and A. D. Jackson, The Nucleon-Nucleon Interaction, (1976) North-Holland Publishing, Amsterdam ISBN 0-7204-0335-9

- Linas Vepstas, A.D. Jackson, A.S. Goldhaber, Two-phase models of baryons and the chiral Casimir effect, Physics Letters B140 (1984) p. 280-284.

- Linas Vepstas, A.D. Jackson, Justifying the Chiral Bag, Physics Reports, 187 (1990) p. 109-143.

- Particle data group listing on the proton

- Particle data group listing on the neutron

- ↑ Massam, T; Muller, Th.; Righini, B.; Schneegans, M.; Zichichi, A. (1965). "Experimental observation of antideuteron production". Il Nuovo Cimento 39: 10–14. doi:10.1007/BF02814251.

- ↑ Dorfan, D. E; Eades, J.; Lederman, L. M.; Lee, W.; Ting, C. C. (June 1965). "Observation of Antideuterons". Phys. Rev. Lett. 14 (24): 1003–1006. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.14.1003.

- ↑ R. Arsenescu et al. (2003). "Antihelium-3 production in lead-lead collisions at 158 A GeV/c". New Journal of Physics 5: 1. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/5/1/301.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||